‘A domestic help’, is not just an occupation but a phrase with many layers in itself. In the Indian context, domestic help consists of those unorganised sector workers who are majorly dominated by women, for one. And second, is the fact that the nature of work being reproductive, work of domestic help remains unrecognised as well. The fate of the children of domestic workers is generally a transferred one. This is a story of one such child, who is a girl; a girl to a female domestic help.

Reena (name changed) is a 13-year-old girl, slim and short, chirpy most of the times and looks fond of accompanying her mother to the houses wherever the mother works as domestic help. Reena’s father is a daily wager but most of the time chooses to stay at home and relax and she has three siblings who stay at home. The eldest sister, 17, earns by tailoring and takes care of all the household work (who will also be married off soon), then the elder brother, 15, help neither in household work nor by earning and lastly a younger sister who is still to be mothered all the time. This makes Reena’s mother the sole bread earner and her sister a supportive earner, making the poverty condition quite grave. Reena, back in the days of non-Corona times, used to go to a nearby government school during day time where mid-day meal provided her with food along with reducing distress on the family for one meal. Reena visits a few houses with her mother every day as a helping hand; now when schools are shut she also accompanies her during the day. It has been almost 4 years now Reena has been working as a partial house help and has acquired expertise in chopping vegetables, arranging utensils, cleaning the kitchen and carrying a smile most of the times. She even goes to work in these houses when her mother takes leave as the substitute, but she doesn’t get any salary of her own. Reena is fond of reading Hindi storybooks and most of the time her aunty’s place (where she goes to work) is a mini-library for her. Her day is spent a bit at school, where she is hardly learning much and then working as domestic help. Reena doesn’t have a playful childhood, she has absorbed the idea of domestic work so much that even when she has been asked to not go to work with her mother, she affirms that she enjoys doing it. Such a response keeps the truth under the darkness that if she really enjoys it, or is it a forced occupation that she has been put into at an early age!

The story of Reena is heart touching, simple yet attracts analysis. Her family’s economic structure has pushed her into becoming a domestic help, as with the current training she can soon work in a household individually and earn. However, what remains a question of thought is the fact that even when she is asked to not come to work she takes hold of any opinion by asserting that it is her choice, and her mother doesn’t speak anything. The question of ambiguity sustains that if she works under her mother’s pressure or she has really accepted the hierarchical fate of becoming a domestic help herself? In either of the two options, the fact remains intact that her mother is able to work in multiple houses only because Reena goes along and actually takes care of most of the tedious work, except making chapatis.

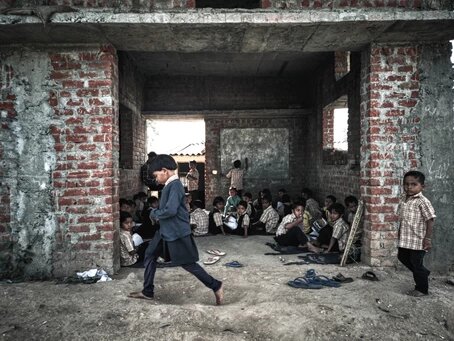

This small case study, although, cannot be generalised because there a lot of domestic help who have chosen a path of granting their children with education and the rightful experience of schooling. Nevertheless, even those fortunate children who get a platform of attaining education by some means struggle on a lot of ends. To begin with, domestic work is highly under-recognised and with scanty labour rights. This plays a very dominant role in keeping the workers from having a rightful holiday from work at least once a week. This in effect keeps the children at a distance from the mother’s attention and monitoring. Also, a male partner’s generic attitude of giving the least heed to the issues of the children leads to children being left not only unattended but also put into easy exposure to bad influences. More so, with a limited or no educational exposure of the parents, the children have a very limited scope of learning things beyond schooling. Not only this, due to the fact that domestic work is quite an underpaid job, poverty remains a struggling aspect always, which situationally pushes the children to take up a part-time job. After a personal understanding of children selling small items on the streets, a pattern can be noted that most of their parents are domestic help, majorly mothers. No matter how rightful schooling and a joyful childhood is, filling the stomachs at the end of the day remains an overarching priority. Or else, there is an unaccounted number of stories like Reena’s as well, being written right under our nose.

However, these are not fateful conditions that cannot be intervened with. In the capacity of being the employers, one has to begin with intensive counselling of their domestic help of not pushing their children into the same occupation, at least at an early age. Second, the domestic workers must be paid living wages and not minimum wages, as most of the times, they are the regular and sole earners in the family. Third, within an employer’s capacity, one must extend support for the worker’s children education, if not economically then by offering a provision of tutoring them at home. These few interventions might not be universal, but can definitely be basic towards helping the domestic workers and shaping a brighter future for their children.